BERLIN – Germany’s energy policy and renewables strategy are heading for a “reality check” under the newly appointed Federal Minister for Economic Affairs and Energy, a former lawmaker returning to politics after nearly a decade in the gas industry.

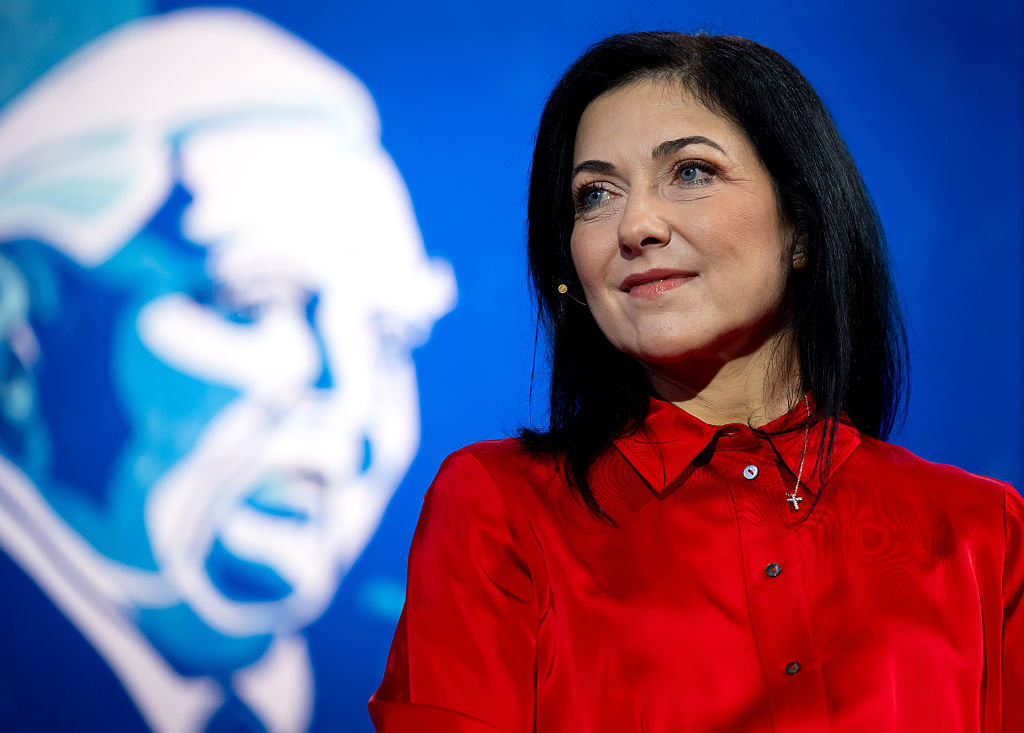

Katherina Reiche, a 51-year-old Christian Democrat, has taken on the unenviable job of heading Germany’s economy ministry, with high expectations that she will turn around the country’s stagnant economy – now headed for a third year without growth – even though authority over key areas, like labour policy and taxation, sit elsewhere.

A core task for Reiche will be recalibrating energy policy to balance a boost for industry while pressing ahead on decarbonisation. Specifically, she will have to implement the coalition agreement’s twin strategy of transforming Germany’s traditional heavy industries to achieve net-zero emissions, while tackling high energy costs that threaten the country’s global competitiveness.

Many in the energy sector and utilities companies see her as cut out for the job, but environmental advocates and climate activists are concerned she remains far too close to the fossil fuel industry after having worked as a lobbyist and executive in the energy sector.

One of Reiche’s first declarations was her commitment to the new coalition government’s plan to build another 20 GW of gas-fired power plants, as well as lowering electricity prices through a mix of subsidies and tax cuts.

She’s also expected to resist the European high-voltage grid operators’ recommendation to split Germany into five separate electricity pricing zones, which the Christian Democrats strongly oppose for fear it could drive up energy costs in southern Germany.

The revolving door

Reiche enjoyed a close connection with fellow Christian Democrat Angela Merkel, and held several senior posts within government ministries during Merkel’s long tenure as chancellor. Both were career-oriented women who grew up in the former East Germany and studied natural sciences before entering politics under a conservative flag.

In 2015, just months after quitting parliament, Reiche was named CEO of the Association of Local Public Utilities (VKU), a trade body representing water, gas and district heating companies, among others. Her refusal to observe a longer ‘cooling-off’ period between holding office and taking the lobbying job drew criticism at the time.

Five years later, Reiche was tapped as head of Westenergie, a subsidiary of energy giant E.ON, which prompted some head scratching among industry insiders given her relatively limited experience. The magazine Wirtschaftswoche described her appointment as “politically driven and controversial” and warned that she was likely “rather naive” about the field.

Industry players have since changed their tune about Reiche.

The German Renewable Energy Federation, a trade association, lauded her last month as “an experienced energy practitioner”, while energy and water utility association BDEW called her “a recognised expert” in the field. The influential Federation of German Industries (BDI) expressed hope she would be the “advocate of the economy” they need.

A lack of ‘critical distance’?

NGO Lobbycontrol, however, has questioned whether Reiche can maintain “the critical distance” from industry needed to make balanced decisions over energy policy.

Reiche has been a member of Germany’s national hydrogen council since 2020, is decidedly pro-nuclear, and sees gas-fired power plants as the best way to maintain energy security. Accordingly, she intends to conduct “a reality check” on the renewable energy expansion propelled by her ministry under her Green Party predecessor Robert Habeck.

Since the release of the coalition agreement, climate campaigners have been questioning the Merz government’s commitment to pushing forward with the transition to renewable energy. Reiche’s assertion that Germany needs “to come clean about the status quo of the energy transition” has only added to their concerns.

Limited room for manoeuvre

Despite being Germany’s economy minister, Reiche’s portfolio has been significantly slimmed down, giving her far fewer levers to pull in pursuit of growth. Under the previous government, Habeck had oversight of digitalisation and construction policies, which have now been spun off into ministries of their own.

Climate policy was also a key part of Habeck’s portfolio. That too has now been shifted over to the environment ministry, led by Carsten Schneider of the Social Democrats.

Reiche’s job was viewed by many as a poisoned chalice. With Germany’s economy trapped in its longest recession in decades, pundits have compared the scale of the challenge to that faced by Ludwig Erhard, the economy minister then chancellor whom many Christian Democrats view as the architect of West Germany’s postwar ‘economic miracle’ of the 1950s and 60s.

A focus on energy

But the leaner look of Reiche’s ministry, which prompted some higher-profile candidates to turn down the job, might end up being a blessing in disguise.

Reiche’s portfolio is narrowly focused on two major sources of pain for Germany’s economy: high energy prices and an inadequate electricity grid. She could also reap some quick political rewards from an economic uptick fuelled by short-term market euphoria during the change of government.

The new economy minister is spared potentially higher-risk policy challenges that are now under the purview of other ministers – such as ensuring Germany catches up in the global AI race, or the daunting challenge of making the high-emission housing and transport sectors carbon-neutral.

Action on climate change, as Reiche said in a recent interview, “cannot be the only goal of the economy ministry”.

(bts, rh, aw)

Source: www.euractiv.com